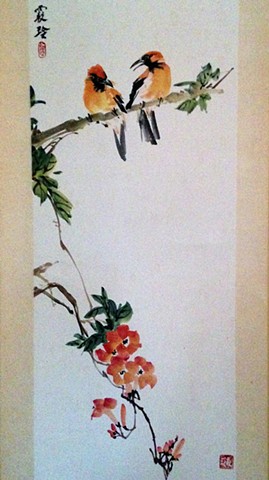

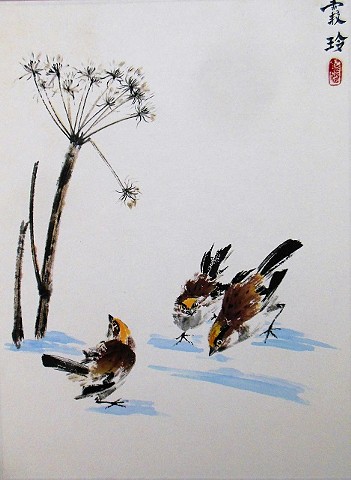

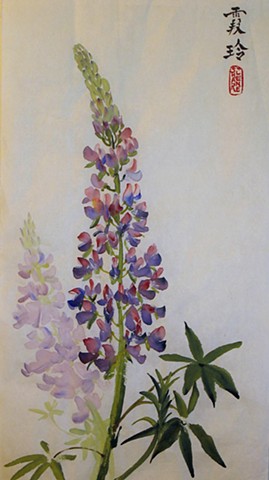

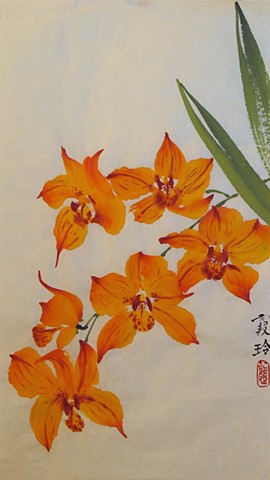

Chinese Brush Painting

Chinese painting demands a meditative mind and a practiced skilled hand. I can only paint Chinese style when I’m centered and calm. In a busy working mother’s life finding, or rather creating, time to paint is an achievement in itself never mind to also sit down with a “still heart.” This calmness is needed to portray the flower and its essence to rice paper. This process is what lures me back again and again to Chinese painting. To me the finished painting is only a byproduct of this process.

The wonder of Chinese painting is that it distills nature to its essence, to its spirit. Mai-Mai Sze’s The Way of Chinese Painting based on the seventeenth century Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting illuminates: Through Tao, the course of nature, is impossible to depict, the aim of Chinese painting is to suggest its presence and reflect its vitality, breath of life (Chi). The painter achieves this by coordinating a still heart and a skilled hand. And in the words of the eighteenth century painter Chang Keng: “Chi is something beyond the feeling of brushwork and the effects of ink, because it is the moving power of heaven, which is suddenly disclosed. But only those who are quiet can understand it.”

In Chinese brush painting a subject is comprised of well-controlled single stokes loaded each time with paint with a mou-bi, a round paintbrush full at the base narrowing to a point. For a flower, each petal is one stroke as is each leaf. This skill takes hours of practicing repetitive brush stroke so that ultimately the hand, coming from a calm meditative mind, knows intuitively how to paint its subject. Like a pianist practicing its scales and pieces over and over again so their performance comes from their soul not just reciting notes.

Another element of Ling Nan School of Southern China style of Chinese painting, other than the characteristic brush strokes and views of nature, is its sense of composition. Empty space and asymmetry are important elements in every painting. It allows the sense of the Great Spirit to be present.

When every stroke carries Chi and the composition includes empty space, it is the end result of the artist inhaling her complicated world, processing it and breathing it anew through her eyes and brush.